Recently we’ve been focused on the Bloomberg/Supermicro/Amazon/Apple supply chain story. But there are other supply chains which are much more common and distributed, and they have been hacked. Lets talk about the ESLint story. Because it happened. Recently.

ESLint is a development tool used in JavaScript & Nodejs. A developer runs it during the build process (during which time it has access to your source code, and also your credentials on the Nodejs registry npm). So as you build your software, a malicious line of code in ESLint is capable of injecting things into your software, and of self-replicating via updating packages you own.

So is this a theoretical issue? No. In July of 2018, ESLint published a post-mortem on a supply chain attack that came through them. So what happened? One of the developers was using the same password on more than one site. Now, you’ve just read that sentence. If you use the same password in more than one spot, stop, go change that. I’ll wait. No really. One weak site can take down a strong one. OK, back? This password was also the only source of authentication (no 2 or multi- factor authentication was used). The weak site got compromised allowing the attacker to uplevel to the npm registry.

So lets think of the timeline. They found this pretty quickly. But they found it by the ‘many eyeballs’ approach, not systemically via signed packages etc. From the instant this was published, until it was taken down, many CI (Continuous Integration) jobs ran worldwide, building new packages and products. And, many CD (Continuous Deployment) jobs ran next, making the code go live. In turn, some of these packages were libraries included into other software. And so on. So even a fractional second of vulnerability in a base tool has a long tail of problems to clean up. Some of those build mid-level libraries might only be built monthly.

In this case, the eyeballs spotted this in about 40 minutes. Sounds like a short time, but, well, npm is seeing ~2B downloads/day. So only 54M downloads occurred during this time. For each one that was ESLint, the attacker got publish control of that next users’s repo. And so on. So all the assurances about ‘we found it quick and reset the tokens’. I’m not sure I buy that the risk is as low as people made out. Someone has control of a wide-spectrum of web technologies because of this.

And recently we have seen British Airways lose customer financial data via their web site. 380000 passengers fell victim to 22 lines of code. We saw this happen with Newegg. Hackers injected 15 lines of code into Newegg’s payments page. This happened to TicketMaster. You can read more about the Magecart issue here.

OK, so what to do? Well, we need supply chain traceability from source line through build process through deployment through operations. Tools to do this are starting to become available (e.g. binauthz). We need some sort of ‘certificate revocation list‘ for open source, something we can quickly hash a file and check if its bad, if others are using it. This is similar in nature to e.g. dns-blacklists. One might be able to use DHT for this as a mechanism. Or blockchain. I want to be able to say “how many people are using this file, how many have reported it good/bad”. Distributed reputation. Make it hard to spoof or influence by making it broad-based.

Its great to use Static Application Scanning (SAST), but the lag time is very long on CVE (first someone finds it, then they allocate a number, go through a coordinated disclosure, wait for the sw to get fixed, … usually 6+ months).

Some say ‘pinning’ is the issue. But, well, you can have problems injected even if the version number stays the same. And the pinned images, do you really go back and update them as they get vulnerabilities fixed? Aren’t you really just locking in the problems?

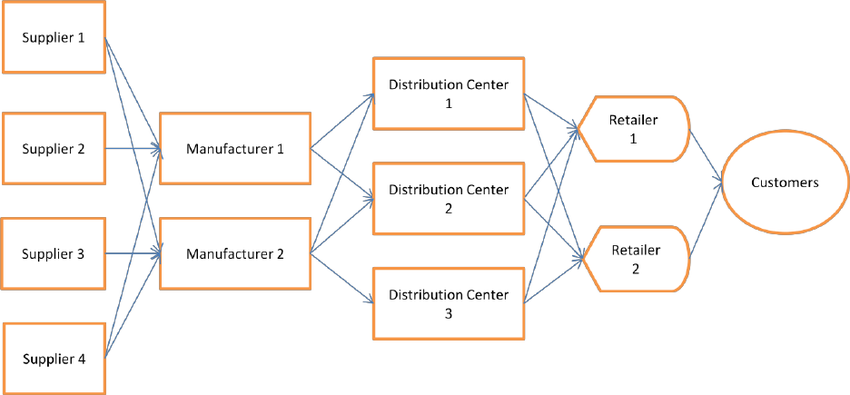

Do you even know the entire supply chain of a given tool you use or create? Its much larger than you think. Go all the way back to source, I dare you. Maybe use a tool like ‘dot‘ and ‘graphviz‘ to show a nice chain. Some research tools exist. But remember, you need to go very far back the chain (remember the famous Ken Thompson hack? It was in the binary of the compiler but not the source).

OK, that was a lot of text. Have fun worrying.

Leave a Reply